If you were to ask me what my favourite programming language is, my answer would be Rust. For the majority of projects I'd prefer Rust to any other language I know. This is not because I simply like the syntax of Rust, but because with Rust I can write code quickly and with confidence that it will work. More so than with any other language.

Rust is correct

First of all, Rust as a language deeply cares about correctness and doing things the right way. This also applies to the ecosystem surrounding the language such as the standard library and the crates on crates.io.

The roots for this sense of correctness might lie in safety guarantees that Rust provides as a memory safe language. Violations of ownership, type or lifetime constraints would potentially lead to undefined behaviour, so Rust has to be inherently pedantic about enforcing such rules in order to be memory safe. But when you work with the Rust ecosystem, you realise that correctness doesn't end with memory safety. It runs throughout Rust's narrative. When you work with functions and types from the standard library, you can feel just how much thought and polish has gone into the design. This vastly contrasts with most other languages I've used such as JavaScript or Java.

Rust inherited many ideas from Haskell and declarative languages in general. Declarative languages come from academia and mathematics. They are what you get when you combine mathematics and logic with computer science and programming languages. For example, they allow to prove the correctness of a program without running it. In functional programming, certain things, like modifying lists, can be done much more elegantly with less code and no bugs. The disadvantage of functional programming is that interaction with the real world, such as talking to hardware and reading user input, is cumbersome. Rust has somehow managed to be great at both things. Rust programs can be formally verified in many ways. The compiler verifies types, ownership, lifetimes and more. You can additionally verify that your program never panics or that it doesn't encounter undefined behaviour.

Rustaceans seem to obsess over seemingly simple things like semantic versioning (SemVer). Developers of Rust libraries won't release the first major version (1.*.*) unless they are sure that their API is mature and stable enough. This process normally takes years and has also kind of become a meme. After the first major release, correct SemVer also means no incompatible API changes with the release of patch (*.*.1) and minor (*.1.*) versions. Complying with those seemingly simple rules turns out to be pretty hard in practice. This is why linters are created to prevent authors from making mistakes.

An example

Recently, I had to deal with dates and date-times in Java. I wanted to validate a string representing a date or date with time and have a type to encapsulate the information. The first type you encounter when looking into this will be java.util.Date. You will notice quickly that most methods on this type are marked as deprecated. When reading about it you learn how it doesn't represent a date but an instance in time measured in milliseconds. Basically, the naming is misleading and the implementation of this type is inconsistent, poorly designed and thread-unsafe.1 This date type was introduced in version 1.0 (1996) and most methods were deprecated in 1.1 (2002).2 So today this type only exists for backwards compatibility, and it continues to haunt developers to this day. Instantiating this type can, for example, be done by providing year, month and day. But remember that the year starts at 1900, the first month is 0 and the first day is 1. Month and day overflows also seem to be a handy feature.

new Date(0, 0, 0) // Sun Dec 31 00:00:00 CET 1899

new Date(0, 33, 0); // Tue Sep 30 00:00:00 CET 1902

The implementation was terrible. After deprecation, you would use third-party libraries instead. This was until Java 8 (or 1.8, Java versions don't make sense) where it was decided to reimplement the date type into the standard library by copying the now popular and established libraries. This implementation was indeed much better, however I still noticed inaccuracies. For example you won't notice when an invalid date in the following case is provided.

DateTimeFormatter f = DateTimeFormatter.ofPattern("yyyy-MM-dd");

// Official documentation

// Throws:

// DateTimeParseException - if the text cannot be parsed

LocalDate d = LocalDate.parse("2021-02-31", f);

// ah never mind, the date is silently rounded off in this case...

System.out.println(d); // 2021-02-28

In stark contrast to Java, the Rust standard library is meticulously correct and polished. Rust developers learned from the mistakes made in the past. Rust is conservative when it comes to adding new features. Only once they have proven useful in other languages or in popular libraries they are considered to be added.

Technical debt

The previous example shows how the concept of technical debt also applies to programming languages. In fact, debt in language design weighs much heavier. Once a language has committed a mistake, it cannot be undone without breaking backward compatibility.

Some established languages have evolved significantly over time. New approaches were introduced to replace existing ones, but the old approaches couldn't be removed due to the need to maintain backward compatibility. This leads to conventions and best practices. Previous best practices become outdated and frowned upon. The language accumulates complexity as its technical debt continues to grows.

C++, for example, has become so complicated over time that "modern C++" conventions have been created where only a subset of the language should be used. Although it is natural for a language to evolve to some extent, too much change can be unhealthy. My feeling about Rust is that its foundations are so robust that it won't change as radically as other languages have over time. Rust guarantees that once a feature is released, contributors will continue to support that feature for all future releases and breaking changes are only introduced in new editions.3

Types

Personally, I think it is a bad decision to use dynamically typed languages for anything other than small projects or scripting. Look at any popular dynamically typed language (Python4, PHP5, JavaScript6, ...) and you will see the same trend; the desire for more type safety. Unfortunately, those languages will never be able to achieve type safety.

Some people, especially beginners, think languages without static types are "easier". Every programming language (maybe with the exception of assembly) has some sort of type system. The main difference between statically and dynamically typed languages becomes apparent when programmers make mistakes. With statically typed languages the compiler complains about the mistake. In dynamically typed languages the program will crash at runtime, or worse lead to subsequent bugs that will be noticed only much later. Catching errors at runtime, perhaps in production, is far worse than a compiler error message. So it would only seem natural for programmers to prefer statically typed languages, unless you never make mistakes.

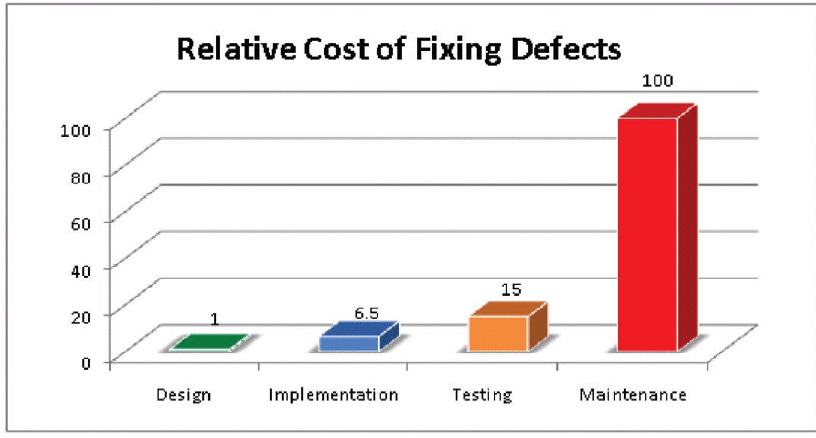

It might be obvious that problems caught in production are worse than problems noticed during implementation. But the effective cost difference is huge. IBM showed this in a study conducted in 2010.

Static types don't automatically lead to type safety. For example in Java you can do the following to trick the compiler and cause a runtime error:

int x = 42;

Object forgetCompileTypeInfo = x; // everything is an object

return (String) forgetCompileTypeInfo; // oh no, a runtime error

In Rust that's not possible. Casts must be valid at the type level, or else they will be prevented statically.7 Not checking for type constraints at compile time, or worse, doing conversions at runtime to somehow satisfy type constraints, as JavaScript does8, leads to more bugs and costs.

No billion-dollar mistake

Many languages have incorporated the concept of lack of value into the language, with special keywords like null, nil or similar. Any time you pass a value by reference, which is the default in many languages (Java, C#, Python, ...), the value can be absent. This concept was introduced by Tony Hoare into ALGOL and has become the norm for most programming languages. However, introducing such a special value that can be present everywhere in the system by default, means you have to handle the special value everywhere with additional code, otherwise you might create bugs. Conventions and best practices started to appear, about when to use this special value. Over time people started to agree that this special value shouldn't be everywhere by default. The inventor himself apologised for introducing the concept in the first place.

But I couldn't resist the temptation to put in a null reference, simply because it was so easy to implement. This has led to innumerable errors, vulnerabilities, and system crashes, which have probably caused a billion dollars of pain and damage in the last forty years.9

Rust is one of the languages which does not know a special null value.10

You must opt in for the possible absence of a value.

This is done with the Option<T> type.

Error handling

Most programmers today agree that using the GOTO statement in high-level languages is bad practice.11 It leads code that is more difficult to read and maintain. I think exceptions like they are known in many modern languages are just fancy GOTO statements. When an exception is hit, the normal execution flow is stopped and the instruction pointer jumps into some error handling section.

Calling any function can throw an exception and the programmer may not realise that this can happen, unless it is documented and the programmer cares to read the documentation. You can't ever know for sure when you should surround a function call with error handling code, unless you establish some sort of convention or documentation. Some languages have "checked" exceptions which force the programmer to either handle the exception or propagate it further, but by requiring annotations. This way you can't forget about handling an exception. However, where there are "checked" exceptions there still are "unchecked" exceptions which can be forgotten about.

In a sense, Rust only knows "checked" exceptions, but with a very different syntax.

Instead of throwing an exception we simply return a Result<T, E>.

The result's value can be either Ok(T) (Ok with a value of T) or Err(E).

You will be forced to check if the result is Ok or Err if you want to access the inner values T or E.

Now there are certain scenarios where your program reaches a state where you can't or don't want to recover, when encountering a problem.

In this case it's possible to panic. When a program panics it will crash by unwinding its call-stack, optionally printing a stack trace.

So Rust's approach is simple and pragmatic. A fault condition should be either recoverable or not.

Error messages

Error messages in Rust are awesome. They're super helpful, concise and correct. As the compiler itself is very strict in general you will encounter compilation errors where you don't know how to resolve the issue and you have to rethink your approach. But the error messages are as helpful as they could possibly get. An unspecific or unclear error message is considered a bug by the Rust team, and you should report it if you ever encounter one. Some compilers give vague error messages and some even point to the wrong source files! This for example happens when working with templates in C++. Working with such error messages is a nightmare.

Runtime errors in Rust are a rarer phenomenon but they will be just as clear as the error messages by the compiler. Most of the time the concise messages are enough to track down the mistake. Optionally backtraces can be enabled as Rust provides a tiny runtime.

If you create a stack overflow with C++ the error message could look like this12:

HelloWorld.exe (process 15916) exited with code -1073741571.

Or it might look like this:

Segmentation fault

With Rust the error message looks as follows:

thread 'main' has overflowed its stack

fatal runtime error: stack overflow

With Rust you don't have to be a coding wizard to understand error messages.

In my attempt to create a stack overflow in Rust, the compiler also warned me about the fact that my function cannot return without recursing.

Dependencies

When writing software these days, you will probably sooner or later depend on external libraries.

This is why dependency management shouldn't be a pain.

Many languages evolved before streamlined dependency management was a thing.

NPM, the package manager for NodeJS, was the first dependency management system I used that I liked.

It became very popular and might be the reason why NodeJS itself got so popular.

Rust's build system and package manager, Cargo, is very similar to NPM with a few improvements.

With NPM, for example, I regularly forget to install or update the dependencies with npm install, whereas Cargo does this automatically for you.

Most languages still don't have an official or standardised way of managing dependencies. Java has Gradle and Maven, both of which seem overly complicated to me. C and C++ have a dozen different unofficial package managers. As of 2024, the most popular registries vcpkg and Conan contain less than 3'000 packages. Cargo has 160'000 packages and NPM more than a million. Python was ahead of its time when introducing pyinstall, which was later renamed to pip, in 2008.13 However, pip hasn't evolved much since that time. Packages are installed globally by default. You will need to make use of an additional package (or better Nix) to avoid breaking the dependencies of your system and to avoid conflicts. Cargo makes managing dependencies and building your project as easy as it gets.

Rust is practical

Rust is surprisingly practical and ergonomic to use from a developer's point of view.

The type system is very strict, but type annotations are often optional because they are inferred.

Prototyping can be easier than in other languages by making use of the todo macro.

Don't know what to return from a function yet? Simply return todo.

Even though there are debuggers, printing variables and variable names is something developers do way too much.

Just use dbg to print whole expressions with their value, file name and line numbers.

To clone or compare objects you don't have to write boilerplate code, you don't need any libraries and you don't need much experience.

You just mark a structure with Clone or Eq, that's one simple line of code.

You like linters? Rust comes with Clippy ![]() ,

the most strict and annoying linter.

Have you made enemies by fighting over code formatting rules?

In Rust, the war is over because there is the official style guide,

which you never have to think about because your IDE or editor uses rustfmt anyway.

,

the most strict and annoying linter.

Have you made enemies by fighting over code formatting rules?

In Rust, the war is over because there is the official style guide,

which you never have to think about because your IDE or editor uses rustfmt anyway.

Compilation times

When people complain about Rust they often mention compile times. It's true that compilation of Rust projects do take their time. But compiling C++ or Java projects really isn't any faster. Given Rust's abstractions and complex rules, I'm actually impressed that Rust is on par with other languages. In practice, compile times rarely bother me. I recompile my Rust programs less, because more bugs are caught by rust-analyser in my IDE, rather than during test execution. Compile times have improved over the last years and they will continue to improve. If you have issues with compilation times there are many ways to further improve them.

Hard to learn

The Rust compiler is strict, that's no secret. As a beginner it can be difficult to get basic programs to compile. Understanding the concepts of the language such as ownership is therefore essential. Fortunately, the official Rust book is perfect for learning all these concepts, and the Rust compiler will also help you along the way. You will encounter compilation errors probably more often than in any other language. There will be cases where you have no idea how to fix the problem at first. Eventually, you might realise that you will have to rethink your whole approach to the problem.

This was the hardest part for me (and still is) when working with Rust. Sometimes the compiler forces you to rethink your approach. You realise that you can't bend the borrow checker to your will, instead you have to work with it. The compiler is your mentor not your enemy to fight.

Personally, I started learning Rust during the Covid pandemic. At the time we had a course on algorithms and data structures at university and I decided to implement the exercises in Rust instead of Java. After reading the first few chapters of the Rust book, I felt confident enough to give it a try. I was able to implement some algorithms and was happy with the results. But I got lost and confused when I tried to implement a binary tree myself. After trial and error, I did some research and came across a chapter in the book I hadn't read yet. Turns out that data structures in Rust can get complicated very quickly. On top of ownership you also need to know about smart pointers, interior mutability, reference counting, reference cycles... I was overwhelmed and discouraged. But I realised that data structures were not the best starting point for learning Rust. And that in the real world you would make use of the standard library and crates built by smart people anyway.

After that, I tried to implement simple things with Rust. Over time I almost forgot about the concepts I read about when dealing with binary trees. It turns out that programming "normal" things in Rust is much easier than I thought. The only thing you really need to understand is ownership. Understanding lifetimes, interior mutability, etc. is great, but in "normal" code you almost never make use of these concepts.

Conclusion

In my opinion, Rust is the pinnacle of modern compiler and language development. The deliberate design choices in the language show how the developers have learned from the problems in other languages. In Rust it might be harder to get a program to compile. You need to understand some basic concepts that might not exist in other languages, but the Rust book provides you with all that knowledge. You might spend more time addressing compilation errors and thinking about how to solve a problem than in other languages. But all this will pay off when your program compiles, because you will rarely run into unexpected problems at runtime. Rust forces you to think hard up front, but rewards you in the future with far fewer bugs and lower maintenance costs. This makes software development more sustainable, and since most of us prefer to write new code over fixing bugs, it could make our lives more fun again.

Python introduced type hints in version 3.5 to integrate with third-party tools

PHP introduced type declarations starting with version 7.4.0

TypeScript is often a preferred alternative to JavaScript

Some conversions in JavaScript are so obscure that you could be called crazy if you understood them all. Put your knowledge to the test with eqeq.js.org

There is a null raw pointer in Rust. But this is normally only used for FFI, i.e. when interacting with C functions